What is content?

Content—we’re led to believe—is a little like the words making up this sentence you’re now reading. Individually, the words mean very little. Sure, you could look up their definitions if you’re so inclined. You might even already know the meanings. I suspect you do. But individually, words mean little. It’s the context around them—the sentences—that provides their meaning and intent. That’s what we’re led to believe anyway.

Content—we’re led to believe—is just words. It’s harmless. It’s just content. It means nothing and has no intent. It’s not designed to influence you, advertise to you or make you feel bad. As we all know, words aren’t harmless. Words have meaning and they certainly have intent. They can hurt us, damage us, influence us. Content is bad. Not all content, but a lot of it. And that’s what we’re gathered here to discuss today.

We’re here to discuss it because the last couple of months I’ve been trying to explain the idea of bad content and faced difficulty in doing so. Not a difficulty in me explaining it—I do that nearly every day on twitter. But a difficulty in other people’s beliefs. There’s a belief that content can’t possibly be bad, despite me attempting to explain otherwise. I started getting quite a few retorts on my anti-content twets. Here’s a not-so-ironic list of 7 things I will now paraphrase that people say to me often.

“Why is content so bad Craig?”

“Could you please help me understand why content is so bad Craig”

“Can you list your detailed reasons and intentions for trying to convince me that content is so bad Craig?”

“Craig, here are my detailed reasons and intentions for why content is a good thing and not a bad thing”

“Craig, you’re wrong”

“No Craig, I really think you’re wrong”

“Craig, this is me angrily saying you’re wrong in more words and syllables but putting the word fuck in there too to show you I’m very angry”

As a result of me being held up as an out-of-touch martyr I have commenced a no-holds-barred war against content. I started a podcast called The Wednesday Audio that spends the majority of its time bashing content unashamedly. A repeated tactic I use is to bleep out words like “content”, “value”, “optimisation”, and other pseudo-nonsense that we’ve developed in this crazy new post-meaning world.

My tweets are no different. I’m often found ripping into people’s stupid engagement tactics that mostly consist of threads, replying for replying’s sake, and Twitter’s seemingly endless love affair with James Clear’s Atomic Habits.

Suffice to say, I bash content almost constantly but I very rarely explain myself. In my online world that’s fair. I jokingly say: “never back down, never apologise, never start again”. Well, I’m not here today to back down, apologise, or start again. But I am here to explain myself. I’m going to attempt—no matter how futile this is—to definitively and explicitly state my stance on how we got here and what content is. Next time I’ll tell you why I think it’s wrong and what we should do instead.

This article will be long. I won’t edit it down. We’ve got a lot of important points to consider and we’ve got a big and important argument to make.

If you’re currently deep in Contentalife, give me the benefit of the doubt. Hold your judgments for 20 minutes or so. Stop reading threads. Close Twitter. Throw Atomic Habits in the bin and please don’t attempt to create a summary of this article so you can make a stupid 7 step breakdown thread on Twitter.

Just try and pay attention.

How we got here

Believe it or not the web is already 30 years old. When the first web page launched in the early 90s, little old Sir Tim Berners-Lee—I don’t think—could have imagined what he was unleashing onto the world. Originally planned as a research project and designed to make sharing research papers easy for people all over the globe, it began with very noble intentions.

I don’t think little old Sir Tim Berners-Lee ever envisioned us posting nonsense short messages on websites telling people what we were doing every second of the day, taking nonsense selfies of our nonsense food instead of eating it or productising our entire non-personalities to film ourselves doing nonsense things so we can sell non-products. I don’t want to put words into little old Sir Tim’s mouth…but I don’t think this was his intention.

The web as a typographic medium

No, the web began from humbler and more noble beginnings. Even as more people other than researchers and big brains started using the medium more, it was still a majority typographic medium. Styling and support for images and video was basic. Large files would take forever to download, so people didn’t use them. They relied on websites structured with text to get their message across.

This meant that people would write things. I know this is incredibly hard to imagine now, but people used to keep personal websites that were full of these things called articles and lengthy blog posts where they just talked about their lives and things they learned. They couldn’t put it into a 30-second Insta Story and couldn’t pepper it with too many photos. They had to describe things with words.

The web as a personal medium

This led to an early obsession with personal blogs across the web, with platforms like Blogspot, Movable Type and WordPress giving people tools to make their own websites. HTML was simple back then, so enthusiastic amateurs could easily make and maintain a personal website where they could describe things with words and people could reciprocate by reading those words. And the words were more than 280 characters. I know, it’s hard to imagine.

The web was personal. The web was barely monetised. The web was social. In fact, everybody was in chatrooms. The web was fun, maybe a little bit Wild West, maybe a little bit dangerous, maybe a little bit edgy.

Content was just a thing you wrote on your personal blog or read on other websites. The only activity you could really do on the web was read things or make things. Everything else was just too difficult.

The web as a social medium

If we travelled all through the 90s enjoying a personal tint to the web, the 00s was a time when the web started to become more social. We’d seen this early on with chatrooms and newsgroups, and now people were playing with these instant messaging platforms called MSN and AIM.

The early 2000s brought us the first proper “social network” that managed to figure out how to pitch itself to teenagers: you could make a social page for your band and upload your band’s music. It was called MySpace, and it was about to change the way we thought about the web forever.

As an enthusiastic geek at 15 years old in 2002, I drop in right around here. I got my first computer when I was about 12 or 13, but I didn’t get the internet until I was a little bit older. I spent my early teens messing around in a bootleg copy of Microsoft Publisher making fictional posters and newspapers just because I enjoyed playing with the tools. I didn’t know it at the time, but this thingymabob-hobby-activity was called “design” and I’d end up doing it as a job.

So when I finally got the internet around 14 I spent a lot of my time on the “social” side of the web. I used MSN a lot, talking to my friends after I’d just spent all day talking to them at school. This was to become my touch typing training for the next 3 or 4 years, sitting at my computer most days bashing out messages to my mates.

But there was this other thing called MySpace that people were starting to jump on. A couple of my friends had told me about it, so I decided to punch it into Internet Explorer and wait for 30 seconds. Those 56k modems were quite slow weren’t they? It gave you time to contemplate and imagine what delights might be served to you when the website finally opened.

There it was. MySpace in all its glory. MySpace didn’t call itself a “social network”, but that was a term other people were bandying around. I didn’t read the news or pay attention to cultural affairs at 15 years old, so I wouldn’t have been aware of such terms. But I was instantly aware that there was something about this MySpace thing. It looked fun in a way that I’d never seen other websites look. I looked at my mate’s profile. It was all crazy GIFs and colours. Probably the most crazy and colourful web page I’d seen in my tiny experience of the web so far.

I wanted one. So I hit signup and proceeded to craft my own profile. My mate told me I could copy and paste some CSS into my profile box and it’d change what the page looked like. I could change the colours and add in crazy GIFs like on other profiles. It was probably the first time I’d been able to express myself publicly on the web and it felt amazing.

And that was it for MySpace really. There isn’t much else to say. I sent messages to my mates. I looked on their profiles to see what they were saying or doing, but there wasn’t much else to it. No timelines, no algorithms. No toxic engagement tactics. No endless notifications when somebody marries, divorces or goes into a relationship. It was a very innocent social network by today’s standards. It opened the doors to the idea that the web could be something else other than all those boring articles and reading. It was a place to hang out, as the Americans would say.

It was the first time that the web started to switch away globally from a typographic medium to Much More Than A Typographic Medium.

The web could be anything, and on the web you could be anything.

The web as a currency of likes

MySpace fell as quickly as it rose, mostly because a little idea called Facebook was stolen from some other people by a little guy called Mark Zuckerberg. After a few years of MySpace I started to hear about this other thing called Facebook. It was better than MySpace I was told. It was cleaner, easier to use. You couldn’t mess with your profile, but it had more features and more people were moving to it.

Facebook was becoming a big concern. By 2020 it would have 1.6 billion users, but in 2005-ish it was much less than that. I saw the same thing I’d seen with MySpace the first time: my mates started talking about it, then everyone started talking about it, then everyone was on it. Facebook didn’t hide away from the idea of being a “social network”, and I might even remember that it used the term somewhere on its homepage. It was somehow more corporate—even back then—than MySpace. More serious and dedicated to its world domination plans.

Around 2007 they triggered one of the first and probably most influential features they’d ever create, the feature that I’ll later try to convince you has led to our world of content: the humble Like button. Poor Justin Rosenstein was just another guy working at Facebook, trying to innocently make Facebook better. To create a positive reinforcement to make content, Justin and his team created the ability to “like” status updates. It didn’t end so well: Jason has since deleted his Facebook profile, said several times publicly he wished he’d never invented the like button and didn’t really consider the psychological effect of such a simple mechanism.

But it’s interesting. For the first time on Facebook, I had a reason to keep my profile updated. If I posted a life event, it might get liked by others. And if it did, others could see that it had been liked. The feature expanded further when Facebook introduced The Wall—a way to post status updates. Facebook became addictive. Whether it was a positive or a negative addictive I’ll let you decide, but it was the first creation of a Pavlovian type response on social networks. One of many tactics that would follow from Facebook.

Later—much later in fact—Facebook would introduce the idea of being able to publicly like anything all around the internet. This would lead to much of the world that we’re now faced with: content created purely for engagement. Content created purely to be shared. Content created purely to be liked. C*ntent.

The web and the rise of algorithms

As you’ll have no doubt inferred during this article, I look fondly on the Old Web. The web that existed pre-like button. The web that existed pre-social network. The web that was simpler, text-based and full of interesting and interested people.

The final nail in the coffin of the Old Web wasn’t really delivered by the Like button. Whilst it went some way to keep millions of people glued to Facebook, it wasn’t the thing that glued people to Facebook. You needed something new to see every time you came to Facebook and if you only had a small amount of friends there just wasn’t that much going on. You could get away with checking it once a day, maybe once every few days.

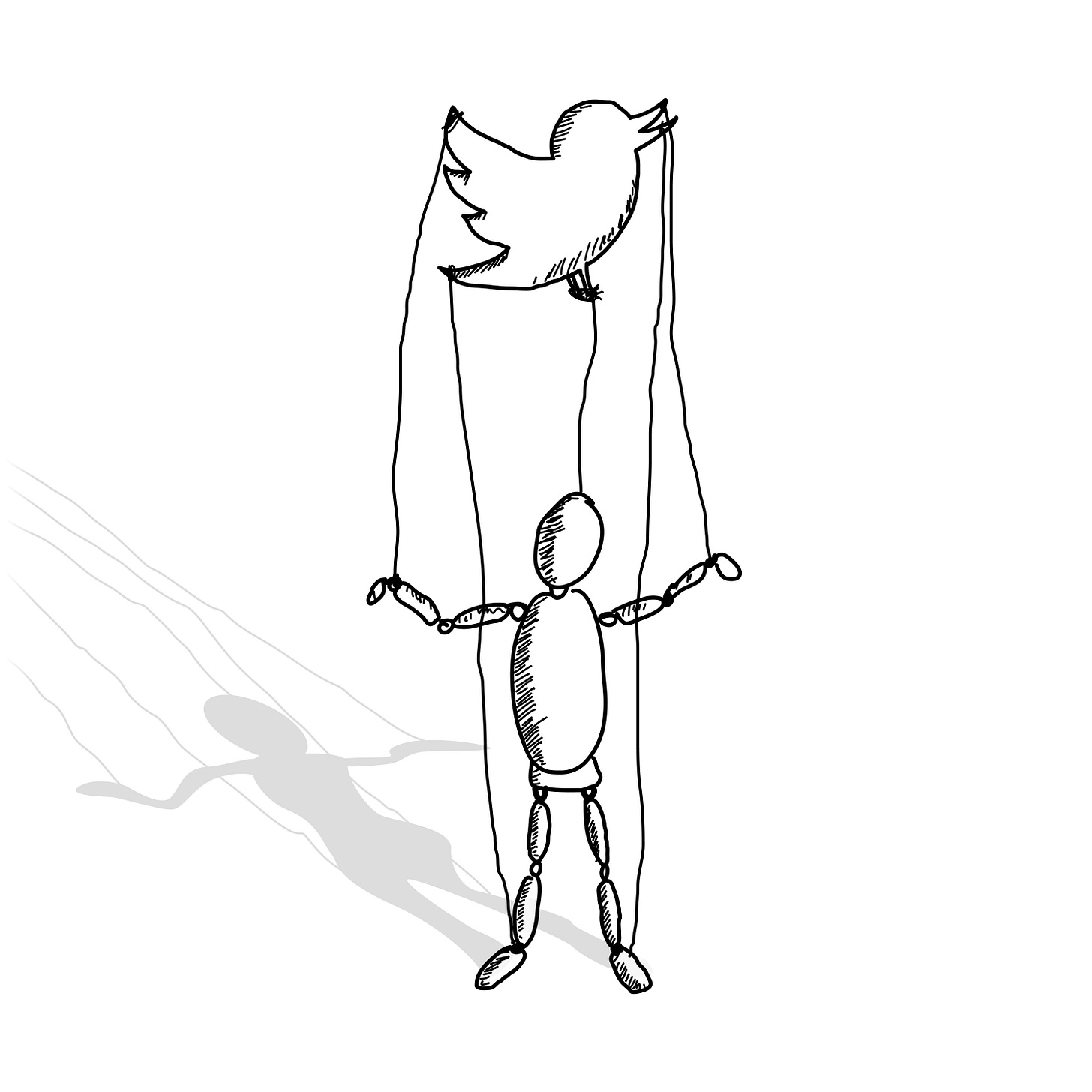

The final nail came when Facebook changed how the feed worked—the thing that you saw when you logged in. Once a simple list of everything your friends were doing, it became a list of everything your friends were saying. Facebook introduced “status updates”, stolen straight from an upcoming social network called Twitter. Then it became different. They began to control the order of the content you received on your feed with an algorithm.

The problem with the early feed was that it was chronological. It was only showing things from your mates and if your mates didn’t do much there wasn’t much to see. So how could Facebook make sure there was always something new to see? Well, they just jumbled the order up and showed you old content from days ago. Later on they’d begin to combine the like button and the feed together, using the like button as a little spy. Everything you liked on Facebook built up a profile of things you were likely to like in the future. Then all Facebook needed to do was serve that back to you in a different order each time.

The rest, as they say, is a deeply complicated history and present that we’re currently living through. I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say that the Facebook feed and its nefarious pursuit of keeping more people addicted to Facebook has led to more harm to humans than any other influence in the last 10 years.

But I’ll row back a little from that viewpoint, because we’re not quite friends enough yet for you to allow me to expose you to the geopolitical makeup of the world and why it’s all Facebook’s fault.

Let’s just deal with content first.

What is content?

We needed to go through that pottered history before we arrived to today. Right now. Through a complicated cocktail of social networks, Like buttons and algorithms we’ve arrived at a messy and muddy present that’s difficult to decipher. It’s hard to work out what’s content and what’s not. I know that. I get that. I know it’s not always useful for me to rail against the idea of content.

But I do, because I believe it’s honest work to rail against content. Necessary work. I know that might sound a bit over-the-top, self-important even. But I so passionately target “content with a capital F” because I believe it’s making us think less, do less, and just be less. It’s allowing us to hold ourselves to lesser standards. It’s allowing us to get away with doing just enough, kicking the can down the road instead of focusing on artistry.

But before we get to artistry, we should talk about “content”. I know there are people out there—and you may be one of them—who don’t even know what content is. To some, content is just words or images or videos. It’s just stuff. They don’t differentiate between a TikTok video or a classic movie. They don’t differentiate between a tweet and a classic book.

Today, I would like to present some differentiation. Over the last 17 years of working in marketing I’ve seen the idea of content become more prevalent and more insidious. More recently I’ve seen the idea of being a “content creator” become popular, even desirable. But I think as we go deeper down the content rabbit hole, you’ll begin to understand my issues with it.

You’ll begin to bleep out the word content just like I do.

“Where’s the cut-off?” I’ve been asked many times.

“When does good content become bad content?” I hear you scream at me from the back of the room.

“Why should we even care? Live and let live etc.” some of you might even mutter under your breath.

“Fair points, fairly delivered” I would say to the fictional selection of audience members I made up to keep the story moving along.

Let’s begin with the cut-off then loop back around to some of these other questions.

Content and C*ntent

There’s content, and there’s c*ntent. In my day job running a design agency, I deal with content a lot. I ask clients to send me content for their new websites. I ask clients to send me content for their new brochure before I can design it. Content is the generic term for “a thing”. A video, a photo, some words, an article, a tweet, a Facebook post, an Instagram post, a TikTok video, a podcast, a piece of audio, music, anything really. A piece of media. Something that says something to somebody.

When we talk about content like this we’re using content in simple terms, as a noun with no loaded meaning. I believe any of the above examples of content can be good content. Just because it’s a TikTok video doesn’t mean that it has to be “content with a capital F”. The medium doesn’t discount its effectiveness or artistry. I don’t rail against content purely because it’s content. That would be ridiculous.

After all, everything is just content. Even the things that we would classically hold in higher regard such as the Mona Lisa, The Sistine Chapel or some new random piece of nonsense that Damian Hirst copied from somebody but sold for millions—that’s all content. It is something that says something to somebody.

Confusing matters further here is the fact that I won’t enjoy the same things that you enjoy. Most of us have a tendency to say that things we don’t enjoy are artless, rubbish, or not worthy of anybody’s time because they aren't worthy of ours. I love Stewart Lee the comedian, but many hate his seemingly rambling form of comedy and the way he never seems to do any actual comedy.

My podcast—The Wednesday Audio—will seem like one man slowly losing his mind to many. It’s random, chaotic and difficult to parse in nearly every episode. You need to have listened to every episode to understand all the in-jokes. I talk to myself, I shout off-mic, I use random noises and sound effects regularly. But regardless of your opinions of it, it’s impossible to categorise as c*ntent because it doesn’t hit many of the 7 categories I list below.

In my descriptions and definitions here I’ve attempted to clarify c*ntent. This isn’t my personal opinion on any particular medium or message, it’s a collection of traits and intentions that I believe makes something ultimately bad content.

I believe the line where something goes from good to bad content involves either one or several of these traits:

The removal of I — The work attempts to hoodwink you into believing it’s an external opinion based on research when it’s actually a personal opinion.

Meta-content — The work is commenting on something else and never makes reference to itself or the fact this is taking place. When done right this is satire. When done wrong it is c*ntent.

The Hidden Advert — The work’s intent isn’t made clear on purpose. Example: a piece of work is arguing a viewpoint that is only being argued because they funded the work.

The Overt Advert — The work exists solely to drive you to consume another piece of work, sell you something, or promote something else.

The Lock-In - The work exists solely to keep you on the platform where you chose to consume it, utilising tricks and platform hacks designed to keep you scrolling. This takes many forms, but often plays with controversial topics to spark your emotions to get you to comment and argue.

Artless — The work contains no attempt at artistry. No attempt to advance the medium, no attempt to subvert the medium and certainly no attempt to create the best work possible. This equally could be described as work that doesn’t take a position.

Gets worse with time — Bad content ages poorly and becomes irrelevant from the moment it’s published. Good content can be returned to at a later date and it continues to improve. Multiple visits to the work will allow you to see hidden layers you never noticed before. Some may call this “timeless” or “classic”.

Let’s study these traits in more detail.

The removal of I

The removal of I — The work attempts to hoodwink you into believing it’s an external opinion based on research when it’s actually a personal opinion.

This is a common tactic in the self-improvement/self-delusion world. As the theory goes (and I know this because I’m in marketing):

In order to appear as an expert one must present themselves as an expert.

It makes sense, at least superficially. After all, content is what everyone can make, so we’re told. The fact that you can remove the author and an appearance of an opinion to increase authority only serves to make it more generic and less offensive.

This is often done with nefarious and chintzy tactics, principle of which is to present your personal opinions not as an “I think this is…” but as a “This is the way it is…”.

Art on the other hand is something only you can make and that scares people. It’s unique to your voice, your way of thinking and your way of seeing the world. Most are afraid to present their work in such a way because when somebody criticises the work it will offend them.

This is how we end up with The Removal of I.

There are times when this is appropriate, just like in this sentence you’re reading right now. Also, it’d get tiresome for me to write “I think this…” at the beginning of every sentence. But it’s not just an active avoidance of the pronoun I’m getting at here. It’s an active attempt to make the article seem authoritative when it isn’t. As the theory goes:

In order to appear as an expert one must present themselves as an expert.

People will use phrases such as “Studies say…” or “The common belief is…” or “As the theory goes…” to increase their perceived expertise by presenting themselves as an outside voice. Now, you know as well as I do that most writing—even apparently objective writing—is fiercely subjective. If you’re going to present your work as “objective”, at least be honest about it. I can’t abide subjective work presented objectively and it’s a gigantic red flag when it comes to spotted c*ntent.

Meta-content

The work is commenting on something else and never makes reference to itself or the fact this is taking place. When done right this is satire. When done wrong it is c*ntent.

Meta-content are truncated versions of a longer piece of content. It doesn’t attempt to review something or provide critique. It isn’t an analysis, although it might label itself as such. In fact, labelling it analysis might even be too strong. It’s just stuff that says stuff about other stuff. Lessons to be learned from something else because it assumes you couldn’t be bothered to read the longer version of it. Breakdowns of movies and lessons learned. Insights into “high-performers” and breakdowns of their methods. In fact, the word “breakdown” is mentioned a lot in this particularly egregious type of content.

You see this endlessly on Twitter because it gets lots of engagement, requires no effort to write and can be repurposed to dizzying levels. It has no bottom level. You can make content about content about content about content about content. You could even write follow-up Twitter threads about why the last Twitter thread did so well. Then make a podcast about that follow-up thread. Then make a YouTube video analysing the statistics.

It truly is utter c*ntent and can go to infinite levels.

Here’s the worst example that comes to mind. Notice also how this thread is presented with a removal of the I (other than the first tweet, that attempts to set it up as personal opinion), as if it’s objectively taking learnings from a tennis match.

The Hidden Advert

The work’s intent isn’t made clear on purpose.

This is the king tactic of most bad content: the reason for the work being made is never made entirely clear. And when the intent does become clear, it becomes clear that the only reason it was made was to sell you something or to promote another piece of work.

Whilst a tweet can be artful, more often than not this is why they end up devolving to bad content. Tweets lack context and nuance and are often being written to promote the writer’s course, book or YouTube channel. They rile up the reader to engage with the tweet and then they attempt to convert that engagement into something else.

Notice I say “hidden intent”. The fact that the intent is to sell you something doesn’t always mean that it’ll be bad content: you can still make artful advertisements after all. But the fact that it isn’t clear if that’s the case is a strong signal that something shady is going on.

A strong example of this are YouTube videos that purport to teach you something. As you get closer to the end of the video, you realise that this video has very little substance. You didn’t learn anything at all. Then the kicker: the video tells you this is designed to introduce you to the topic, and you can find out more by buying the full course.

If the video was up-front about this, of course this wouldn’t be a problem. It’s the fact that this intent is hidden that it becomes a problem. It leads to a distrust of all content.

For me, this is the number one thing I question whenever I’m consuming any content online. If I can’t see why the work has been made it’s never a good thing.

The Overt Advert

The work exists solely to drive you to consume another piece of work, sell you something, or promote something else.

The opposite of the hidden intent is the Very Obvious And Clear Intent. The humble advert.

Some fairly innocent requests might be:

“If you want to see more content like this, make sure you hit Subscribe!”

“If you enjoyed this Twitter thread, make sure you like every tweet and retweet the thread!”

“If this podcast helped you in any way, make sure you leave a review!”

Some more insidious requests could be:

“This is only a preview of my full online course. If you enjoyed this, make sure you buy my full course!”

“Download my 7 Steps to Becoming a Content Creator now!”

Again, it’s the intent. All bad content is an ad, but good content isn’t.

Work that exists solely to drive you to consume another piece of work and (usually) pay for it is very rarely artful or produced with the right intentions. It’s difficult to artfully ask for something and it comes across as desperate.

For example, if my intention for writing this article was to sell you an online course about how to avoid bad content, it would be reasonable to assume I wouldn’t be going into so much depth. I’d leave out the key “secrets” for the course. I’d present the article as “7 things you never knew about bad content”, and finish the article by telling you there’s much more I need to tell you.

When selling or signposting is the sole purpose for creating a piece of work, its intent is different, and the work stinks of said intent. You can smell the desperation and it doesn’t smell good.

The Lock-in

The work exists solely to keep you on the platform where you chose to consume it, utilising tricks and platform hacks designed to keep you scrolling. This takes many forms, but often plays with controversial topics to spark your emotions to get you to comment and argue.

Wherever a social media platform is, it has an algorithm. As we discussed a little bit earlier, algorithms are designed to keep you on the platform and keep you addicted. They’re solely designed to increase a social platform’s most important statistic: Time-In-App.

Time-In-App (it’s sometimes called other things) is a key metric all platforms want to increase. They want you scrolling the platform for longer so you can create more content for them and click on their ads.

To increase Time-In-App, each platform chooses to prioritise certain things in their algorithms that they’ve found are more appealing. On Twitter, these are threads. People spend more time consuming collections of tweets threaded together than they do single tweets at a time.

So, Twitter chose to give this kind of content an artificial boost. If you write a thread, it’ll do better on their platform than single threads will. It’ll lead to more followers, likes and retweets. You’ll feel like you’re progressing and building an audience, and Twitter gets to increase their Time-In-App number from two ends: you spend more time writing content for the platform, and your audience spends more time reading it.

That’s why I’m suspicious of most Twitter threads and any other content using engagement templates. They’re a cheap way to hack the platform and they play on people’s emotions to generally make their lives worse: by encouraging people to spend too much time on social media.

Artless

The work contains no attempt at artistry. No attempt to advance the medium, no attempt to subvert the medium and certainly no attempt to create the best work possible. This equally could be described as work that doesn’t take a position.

This one’s a bit more woolly and often hard to spot unless you’re already in the game (so to speak). After all, what is art? It varies from person to person. One person’s Mona Lisa is another person’s excuse to listen to Lisa moaning about how pants that piece of art is.

I do believe we have a natural ability to spot bad content, even though doing so might be difficult. You might not know why something isn’t very good or seems like no effort was spent, but you can detect it on some instinctual level. You can spot effort. You can spot an effort to advance the medium, to try something different.

Consider Tom’s article on walking. Consider this Two Ronnies sketch about Mastermind. Consider this other Two Ronnies sketch about Four Candles. Consider this Stewart Lee sketch about immigrants. Consider Henry Rollins talking about Iron and the Soul. Then compare those to a Twitter thread about 27 things learned from reading Atomic Habits.

Artless content is just work that’s OK. Average. Generic. And that’s OK—for a while. When we first start making anything we won’t be good at it. Artless work never makes an attempt to improve the standard and will continue to trot out the same work forever.

Work that attempts artistry is a joy to read. Work that makes no attempt is just dull.

Gets worse with time

My description above says all I need to say on this one:

Bad content ages poorly and becomes irrelevant from the moment it’s published. Good content can be returned to at a later date and it continues to improve. Multiple visits to the work will allow you to see hidden layers you never noticed before. Some may call this “timeless” or “classic”.

More than anything, bad content is a choice

You’ll notice that 6 out of the 7 points I make above are purposeful choices you make before starting the work. You don’t accidentally choose to advertise something, overtly or otherwise, or make no attempt at artistry. These choices are made very intentionally to promote something else. The work—as Thomas J Bevan so often says—is a means to an end. The work in this instance doesn’t matter: all that matters is that this piece of work points to this other piece of work over there. And too often that piece of work over there costs money.

Don’t think I’m against making money with our work—I’m not. I just live in a magical hinterland where I believe we should all be attempting to make good work and not phoning it in. So often the call of self-improvement is to try harder and practice more, so it’s somewhat ironic that most work about self-improvement lacks any semblance of skill or any attempt at trying harder.

Meta-content is a choice: content that is about other content. Think of work like this as a gig poster. The band has a gig coming up in a town near you. The gig on the night will be the piece of art, the good content. The gig poster—the flyers stuck all around the town and left in bars—they’re the bad content. If the gig didn’t exist the poster wouldn’t exist. In and of itself, the poster doesn’t need to exist.

Extrapolated out to our online world, you see this game playing out everywhere you look. Just ask: “why is somebody creating this?” Is this a gig poster, or is this the actual gig?

Consider this the next time you’re reading someone’s tweets or watching a YouTube video. What is it selling you? Who is sponsoring the opinions in the work? Will the work improve with time? All of these content traits are a matter of intent, the key indicator that reveals whether something is good or bad content.

So is it bad content or not?

Ask yourself these questions when you’re making a new piece of work:

Am I pretending to be objective in my work to hoodwink someone?

Is this work created just to promote something else?

Am I making this work because I’m being paid to or because I expect to receive other benefits?

Am I advertising a larger piece of work with this piece of work, or trying to sell or promote something else?

Am I creating this work to fit it into an algorithm or formula rather than stand on its own?

Did I rattle this work out as fast as possible with no attempt at artistry?

Will this work become outdated quickly?

If you answer yes to a significant number of these, you’re making c*ntent.

In conclusion

I’ve got more to say on this. So much more that I’ve decided to do the classic bad content move and split this into multiple articles. It might end up being even more than that as we wade the depths. In my view, so much of this becomes a question of morality. Do you want to do the right thing, or do you want to do the wrong thing? Do you want to present yourself as an expert even though you’re not, or do you want to tell people what you really are?

In the end, it often comes down to how many people you want to lie to. Simply, c*ntent lies to people. We have enough of that with advertising and we certainly don’t need any more of it from you. You may have innocently started using ‘engagement’ templates. Writing your 7 Steps To Nowhere type articles, writing threads on Twitter and making your interview podcast that nobody listens to, but more than lying to others, you’re lying to yourself.

But, that’s for the next essay.

We’ll get into that a bit more soon. Go make something that means something instead of something that withers. Hold yourself to a higher standard and don’t stoop to the engagement tactics game.

I honestly believe we don't need it. I honestly believe we're on the precipice of all of this nonsense becoming so transparent that you won't even be able to get away with it in a few years' time. More than anything else, I honestly believe it's bad for our souls. Making bad work makes you feel bad. Whilst that point might feel a bit basic to end this on, I honestly believe too many of us have forgotten even that most basic point.

For now, let’s just go think a little bit about our work a little bit yeah?

You’ve gone a lot deeper into this than I could, I think. I call it being trapped inside the bullshit machine.